In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

Today I’m looking at a book from 1951, Ray Bradbury’s The Illustrated Man, a follow-up to his popular fix-up novel The Martian Chronicles. At this point in his career, Bradbury was still largely a short fiction writer, but he was gaining wider attention and publishers were eager to publish another of his books. Bradbury still hadn’t completed a full standalone novel (that would come in 1953, with Fahrenheit 451), so—as with The Martian Chronicles—they were willing to accept a collection of short stories connected by a framing narrative.

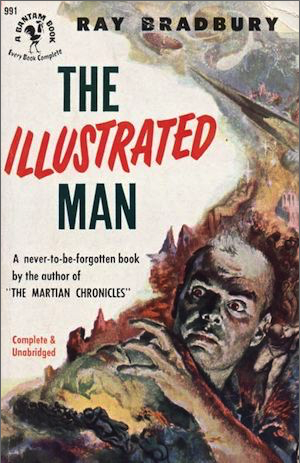

For this review, I’m using a first edition Bantam paperback copy from 1952, discovered at my favorite local used book store. Like Bradbury’s other work, The Illustrated Man is full of cleverly constructed tales, all built with wonderfully evocative prose and brimming with a wide range of emotions. The book was very influential, inspired writers and musicians from a range of genres, and some of the stories served as the basis for a movie of the same name in 1969. I loved these stories when I first read them, even the scary ones, and my most recent reading confirms that I love them still.

About the Author

Ray Bradbury (1920-2012) was a prominent American science fiction and fantasy writer, playwright, and screenwriter, who started his career as an avid science fiction fan. I previously reviewed his 1957 book Dandelion Wine (find it here) a few summers ago. I’ve also discussed his 1946 collaboration with Leigh Brackett, “Lorelei of the Red Mist,” when looking at an anthology containing her work (find it here). And most recently, I reviewed his wildly popular anthology from 1950, The Martian Chronicles (find it here). You can see more biographical information in those columns. There are some earlier stories by Ray Bradbury available on Project Gutenberg, including “Lorelei of the Red Mist.”

The Anti-Science Science Fiction Writer?

In my review of The Martian Chronicles, I pointed out that Ray Bradbury was one of the authors who brought science fiction out of the confines of genre fiction and into the mainstream of popular culture. But while Bradbury often used science fictional elements like rockets, robots, and other planets in his stories, he was uncomfortable with being labeled as a science fiction author. In his Wikipedia entry, I found a quote from an interview that summed up his thoughts on the subject:

First of all, I don’t write science fiction. I’ve only done one science fiction book and that’s Fahrenheit 451, based on reality. Science fiction is a depiction of the real. Fantasy is a depiction of the unreal. So Martian Chronicles is not science fiction, it’s fantasy. It couldn’t happen, you see? That’s the reason it’s going to be around a long time—because it’s a Greek myth, and myths have staying power.

And at some point early in his career, Bradbury must have been perceived as having a bias against science itself. There is a rather defensive blurb on the back cover of the paperback I used for this review: “RAY BRADBURY is a little doubtful of the uses to which certain sciences are being put in the world. He thinks radio, television and motion pictures are wonderful, but decries the hogwash utilized all too often on these mediums by those in control. He believes in atomic power and automobiles, if used with common sense, but also believes that we may very well kill or maim ourselves with these devices if we do not put laws into effect to control them. He is not, as he has often been misquoted, against science, but rather against the mis-use of science by fools.”

But regardless of the labels applied to Bradbury’s work, it was clearly something special. He took themes from science fiction, fantasy, history, myth, and fables, and delivered them with wonderfully poetic prose, infused with heartfelt emotion, and written in a way even literary critics could admire. It is no surprise that, whatever he said about himself and his work, the science fiction community has always been proud to call him one of their own.

The Illustrated Man

This book has a thin but compelling framing device. The unnamed narrator, sleeping rough, is joined at his fire by a man who is covered by tattoos that mutate as you look at them; if you stare at them long enough, they tell you stories of the future. The man is tortured by their images, as they also warn watchers of the threat he might pose to them in the future. This framework allows the stories to cover a wide range of unconnected topics, and a number of those tales are set on the fictional Mars of The Martian Chronicles, a setting Bradbury was not yet willing to abandon.

The first story in the collection is one of Bradbury’s most widely known tales, “The Veldt,” which originally appeared in The Saturday Evening Post. If I am reading the ISFDB website correctly, in addition to The Illustrated Man, the story has appeared in at least a dozen anthologies in English, not to mention being translated into about sixteen other languages. I’m pretty sure my first reading of the story was in one of those anthologies, borrowed from the local library. The story features a “house of the future” of the kind suburban families dreamed about in the mid-20th century, which can do everything its owners desire, not only chores and cooking, but providing entertainment as well.

At the heart of this home is a nursery that can bring anything a child imagines to life, an idea that predicted the virtual reality devices that are beginning to emerge in our own time. But in this case, instead of the antiseptic stories from their children’s books, the children conjure up the image of an African veldt, where a pack of lions seems to be either killing or eating their prey in a perpetual loop. When it comes to horror, an everyday threat presented effectively can beat any Lovecraftian eldritch being ever created, and here it is the amoral greed of spoiled children, amplified by the power of technology, which brings terror to the suburban family.

“Kaleidoscope” is the story of a rocket is destroyed in mid-journey, with its crew now floating in spacesuits, awaiting death. How they face their inevitable demise varies, and there is a bittersweet twist at the end.

“The Other Foot” is a follow-up to a story from The Martian Chronicles, “Way in the Middle of the Air,” in which the Black inhabitants of a southern town hire rockets to Mars, leaving the White inhabitants with no one to persecute. Now, the arrival of a rocket piloted by a white man is anticipated by a Black community on Mars, and among those who flock to see him are people who think they should treat the visitor in the same way they had been treated back on Earth. But when they hear an atomic war has reduced the population to a pitiful few who need to flee to Mars to survive, they see that maybe the old cycle of pain and prejudice should be broken.

“The Highway” is set on a farm along a backwoods roadway in Mexico. The people in the cars rushing by are concerned with nuclear war and the end of the world, but it is all a matter of perspective, as the farmer does not see anything that will affect his own life.

In “The Man,” the self-absorbed captain of an exploration rocket is frustrated by the indifferent reception he gets from natives of a new world. They are all talking about a man who recently visited, preaching peace, and healing the sick, and tell the captain he will not find the man here. The captain goes off to search the next world, not realizing it is his own anger that keeps him from finding what he seeks.

“The Long Rain” follows a military unit marooned on Venus, and here Bradbury’s evocative prose turns the rain and storms into an unending and visceral horror. The unit is trying to reach a Sun Dome, a snug installation that will provide shelter and safety. But storms and setbacks winnow down the personnel until only the lieutenant in charge reaches safety. Because of the madness that infected the unit, however, it’s not clear whether his success is real or imaginary.

In “The Rocket Man,” a young boy and his mother grapple with the frequent and extended absences of the space-faring father, who after bittersweet interludes at home on Earth with the family, always answers the urge to return to the interplanetary voyages that he loves. He is a modest man, and does not like to wear his uniform, but at one point they convince him to put it on, and Bradbury captures the moment with a paragraph I will never forget: “It was glossy black with silver buttons and silver rims to the heels of the black boots, and it looked as if someone had cut the arms and legs and body from a dark nebula, with little faint stars glowing through it. It fit as close as a glove fits to a slender long hand, and it smelled like cool air and metal and space. It smelled of fire and time.” The father finally relents, promising his family that the next voyage will be his last, which turns out to be true, but in the saddest possible way.

In another story set on Mars, “The Fire Balloons,” a group of Episcopal priests travel as missionaries, not to preach to humans, but to the Martians. Father Peregrine—who strikes me as an academic, as his concerns are always of a philosophical nature—travels into the wild with the more pragmatic Father Stone. The Martians they find are floating balls of glowing energy, and save the two priests from a landslide. Father Peregrine then decides to step off a cliff, and the Martians save him again. The glowing beings then speak to the priests about how they have transcended their physical bodies. The earthly Father Stone then has an epiphany that, just like there is a Truth on Earth, there is a Truth on Mars, and Truths on other planets as well, which make up a larger universal Truth. It is an ecumenical message that my young self found far more compelling than the narrow definitions of truth I heard from some of our ministers in church, and still resonates with me today.

“The Last Night of the World” finds that a contented couple might not need to do anything different when they face the end of everything.

“The Exiles” is another tale that echoes a story in The Martian Chronicles, in this case the story “Usher II,” where an eccentric genius builds a technological trap to destroy the government officials who are behind censorship on Earth. In “The Exiles,” the battle with censors is much more symbolic, with dead authors and their fictional creations working together to fight a rocket bringing the last copies of banned books to be destroyed on Mars. The story defies logic, but its emotional core holds a powerful message.

“No Particular Night or Morning” is the story of a space traveler overwhelmed by the immensity of space, and his descent into madness.

One of my favorite stories in the volume is “The Fox and the Forest,” the tale of a couple who travel back in time to avoid a dystopic future where a ruined Earth is plagued by war. Because the man is a scientist whose knowledge is essential to the war effort, they are pursued through time by government officials. But while they are willing to resort to murder to prevent their return, their efforts are in vain, and their fate as inevitable as history itself.

“The Visitor” is a tale in which Mars is used as a dumping ground for people with a new and fatal disease. A new patient arrives—a young man who can create mental images that transport others into a virtual world that helps them temporarily escape their plight. He soon becomes a pawn in a brutal battle over his services, which soon destroys the goose that laid the golden egg.

“The Concrete Mixer” posits a Martian invasion of Earth defeated not by military force or disease, but by overwhelming the Martians with the inexorable force of capitalism.

A man purchases a mechanical doppelganger in “Marionettes, Inc.”, which will allow him to take a vacation from a clinging and oppressive marriage, only to find the robot developing a mind of its own, and deciding to replace him once and for all.

An army unit from Earth moves into “The City,” only to find it uninhabited. But the cybernetic metropolis remembers what humans did the last time they encountered its late inhabitants, and has a plan for revenge. The plot is thin, but the story packs an emotional punch.

In “Zero Hour,” the children of Earth are all playing the same game, called “Invasion,” at the same time, at the behest of their imaginary friend. But if you are alien invaders looking for help from the other side of a dimensional barrier, who better to enlist for help than impressionable young children? And what greater horror can an adult face than having their own children turn on them?

In the last story in the collection, “The Rocket,” Fiorello Bodoni has always dreamed of going to Mars. But the junkyard operator finds he has only enough money to send one family member to Mars, and no one wants to leave the others behind. But then a full-sized prototype rocket is offered for sale to his junkyard—it can’t take them to Mars, but it can allow them to them pretend to take the trip together. Sometimes, the journey is more important than the destination, and this sweetly sentimental story celebrates the power of imagination.

The final segment of the framing device, however, turns to horror again as the narrator looks at the last tattoo on the Illustrated Man, where he sees himself being strangled, and runs away in terror.

Final Thoughts

The Illustrated Man follows in the footsteps of The Martian Chronicles by presenting a wide selection of well-written and compelling tales, but offers an even broader range of topics and subject matter. The stories run the gamut from sweet and sentimental, to wry commentary on the human condition, and even to outright horror. And they illustrate recurring themes in Bradbury’s work, insisting that censorship in any form is evil, and people need stories that spur their imaginations, even when they are unsettling.

Now it is your turn to provide your observations, whether they are about this book, or about Bradbury’s fiction in general. I look forward to hearing from you.